What is Participatory Archiving and Why Does the South Caribbean Need It?

The communities of Caribe Sur have experienced rapid change in just a few short decades.

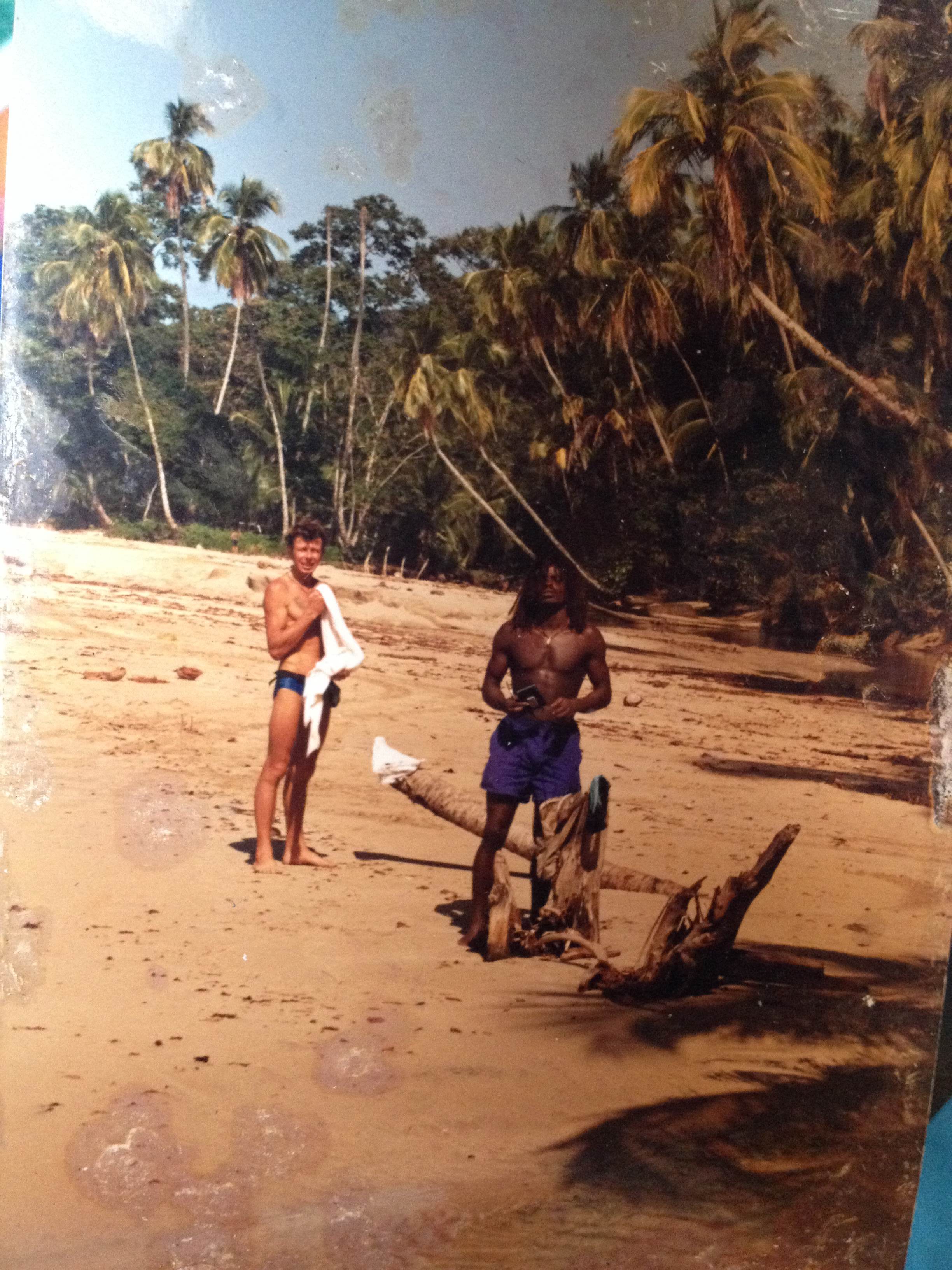

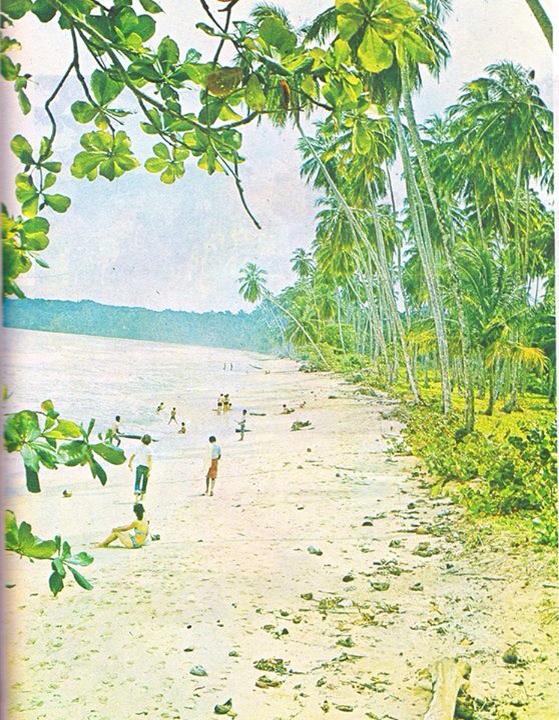

It wasn't long ago that school children walked along the beach to get to school, or that goods traveled between Manzanillo, Puerto Viejo and the rest of the world by boat. Ask anyone who has been here for more than a couple of decades and they remember the days before electricity, even before the road. They recall when the first payphone arrived to town, and can recount the formerly long, sometimes arduous journey to Limón. They'll tell you how just about everyone made their living from cacao, and how a sense of community helped everyone survive by sharing what they had.

Times are different now.

High-speed internet has officially found its way into the jungle and newcomers from all over the world have turned this formerly isolated village of Afro-Caribbean farmers and fisherman into a pluricultural beachside haven for many seeking an alternative way of life off the beaten paths of their varied and far-reaching homelands.

This set of historical circumstances has made the South Caribbean coast of Costa Rica an exceedingly interesting case study in sustainable development, multiculturalism and the possibilities of local ecotourism. It has also presented very real and present challenges to its historic Afro-descendant and Indigenous communities, who's rights to property and development are threatened by the pressures of globalization, climate change, rising inequality, and a history of legislative decisions that do not reflect or respect the particular reality they live, far away from the capital.

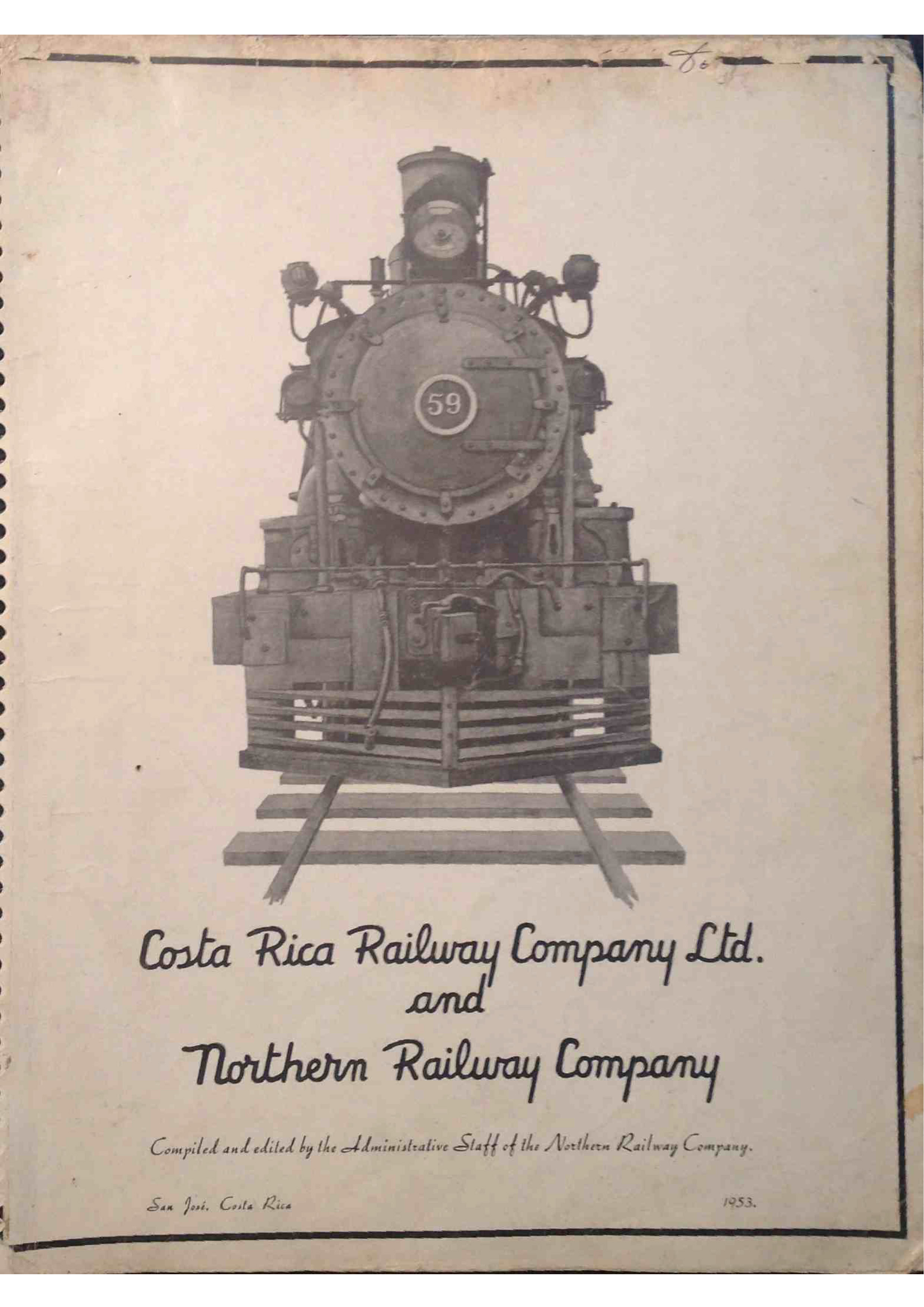

Underlining the challenges described above is a lack of meaningful documentation about the community's history, identity and rights. The written history of the people of the Talamanca coast is scarce, and objective and accessible contributions have not been made for nearly 40 years (see What Happen: A Folk History of the Talamanca Coast by Paula Palmer, first published in 1977). Like many communities of the Afro-descendent diaspora, the history of the Talamanca coast is largely recounted through oral history. With the loss of elders who are willing to preserve and pass along oral histories, cultural memories will vanish unless an active effort is made to preserve them.

Recognizing the vital importance of documenting local history and preserving the individual and collective cultural identity of the south Caribbean, the South Caribe Roots Archive offers one solution to the imminent threat of knowledge loss: participatory archiving.

What is Participatory Archiving?

Participatory archives have been defined as:

An organization, site or collection in which people other than the archives professionals contribute knowledge or resources resulting in increased appreciation and understanding of archival materials and archives, usually in an online environment.

Kate Theimer, The Future of Archives is Participatory: Archives as Platform, or A New Mission for Archives

Participatory archives can serve as an important tool for communities in transition, enabling stakeholders to contextualize the current experience of residents through the lens of a communities' past. Allowing for meaningful participation in the construction of the archives provides an opportunity to honor and preserve the knowledge of community elders while integrating the experience and perspectives of younger generations and the many newcomers who have chosen to call these shores home.

Participatory archives acknowledge that multiple parties have rights, responsibilities, needs and perspectives with regard to the record. They are created by, for and with multiple communities, according to and respectful of community values, practices, beliefs and needs. Participatory archives offer a space for negotiating different perspectives, experiences and needs and a mechanism for reconciling the dual nature of archives that has been critiqued by scholars and distrusted by those who have been disenfranchised, silenced or otherwise marginalized or victimized by archives and recordkeeping more generally.

Anne J. Gilliland - Sue McKemmish: The Role of Participatory Archives in Furthering Human Rights, Reconciliation and Recovery

Learn more about the growing participatory archive of coastal Talamanca

Gilliland further describes the factors that frequently motivate participatory archives, all of which can be considered relevant to the South Caribbean and valid justifications for the work of the South Caribe Roots Archive:

- The identification, collection and use of historical sources to document histories perceived to be ignored or misrepresented.

- Active engagement in the construction of history rather than passive or disinterested curation.

- History-making as a participative practice - as heritage activism.

- Embodiment of DIY cultural and political engagement (i.e., without the aid of “professionals”).

- Making the past “useful” - community-based archiving as social movement activism and mobilization.

- Community-based history-making and archiving for education and identity formation.

- Creating spaces of aspiration and possibility.

- Community-based archives as community-owned space (place of safety, place of resistance, as monument to presence)

Students from Indiana University's Kelley School of Business interview Manzanillo residents Ethlyn Weir and Dennis Clark as part of the Alternative Spring Break collaboration with Kelley Initiatives for Social Impact.

The mission of the Rich Coast Project is to to create a replicable model of community-based human rights advocacy that uses storytelling and digital archiving to foster community resilience, empower citizen engagement, and increase access to information so that local communities may have a meaningful stake in their history and their future.

We work with local and international partners to coordinate projects that investigate the history, identity and rights of the communities of Caribe Sur. We digitize historic photographs and share them back with the community through online galleries and participatory expositions that invite stakeholders to share their knowledge. We interview community members to collect valuable intangible cultural heritage and foster empathy and understanding of the unique experience of area residents. We research topics of local importance to facilitate access to information and empower residents with knowledge of their history and rights.

An example of our work

The timeline below was constructed using the TimelineJS tool from the Knight Lab at Northwestern University, and is a visual representation of photographs and information provided by Christina Zingrich, a longtime resident of Playa Chiquita. A selection of these photographs will be exhibited (with others from the South Caribe Roots Archive) at the Casa de la Cultura in Puerto Viejo beginning November 25, to be later distributed throughout the community. Through these visualizations and public events we hope to, as Gilliland describes, make the past "useful" by empowering residents with information about their past so they can collectively envision "new spaces of aspiration and possibility."

Do you have thoughts on our work? Would you like to get involved? Email us at info@therichcoastproject.org